Feedback is vital for finding out what’s good and bad about an idea and our behaviours. However, feedback is also something that we often dread. The prospect of giving someone feedback can be a gut wrenching feeling and it can feel even worse to receive it! It is unfortunate that something of such value can feel like torture, but it need not feel this way.

In this article we’ll look at: why feedback is so important, how some of the most successful companies use feedback systems, techniques to help make feedback part of your work culture and the best practice for both giving, and receiving feedback.

Short on time? Head straight to our Summary at the bottom of this page.

Why do we need feedback?

The modern world is full of complex problems. By complex problems, we mean challenges that are not solvable through a list of instructions. When dealing with complex problems there are often things that we overlook, or don’t even think about, we can’t see the wood for the trees.

For example, if your television isn’t working you can troubleshoot until you find your solution. Is the television switched on? Has something come loose? Has your partner been changing the wires to connect up to something different even though you had it in the absolute perfect configuration? Is it just broken and you need to buy a new one? It may be a pain but it’s not a complex problem, you just have to go down the checklist.

However, when designing a new product, coming up with a sales strategy or even planning a Christmas party, a troubleshooter won’t cut it. To begin solving complex problems, we need to unearth them through a process of experimentation and discovery. We have to tinker around with ideas and test assumptions.

So where does feedback come into the process of dealing with complex problems?

Even ideas that seem perfect at their conception can fall apart due to unforeseen circumstances or blindspots. Feedback allows us to challenge our assumptions and cognitive biases in the same way that a scientist uses experimentation to attempt to prove their hypothesis. They need to test their theories out in real life scenarios and to fill in gaps in their own knowledge, otherwise their ideas will soon be outdated and useless.

Countering Our Biases

There will be times when we think we are approaching a complex problem with impeccable logic and that we have left no stone unturned. However, the truth is that we are constantly being impacted by various cognitive biases that will affect the way that we approach information.

Cognitive biases are the way we make quick choices and assumptions about the world around us. They’re essentially your brain’s ‘Rules of Thumb’ for decision making. They have some value in allowing us to quickly assess a situation and make choices but like all rules of thumb there are many exceptions and occasionally massive holes in our logic.

There is a comprehensive list of cognitive biases. Today we will look at three which commonly affect our decision-making skills:

- Confirmation bias: looking for evidence that supports what we already believe and attributing less value to evidence that doesn’t.

While researching confirmation bias, Dr. C. James Godwin looked into people who believed they had Extrasensory Perception (ESP). People who believed they had ESP would readily attribute themselves absentmindedly thinking of a parent and then later receiving a phone call from them as a clear sign of their powers. However, they would ignore any incidents when they received a phone call when they weren’t thinking of their parents.

- Availability Heuristic: using immediate examples that come to mind as evidence for your evaluation.

Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman found that people base the probability of an event happening based on the ease with which examples come to mind. The classic example of this is if a shark attack is in the news, the availability of this in your mind will tend to make you more wary of swimming in the ocean.

- Choice Supportive bias: we attach more value to an idea we choose rather than someone else’s regardless of the flaws.

This is very common in meetings, we will often attach more weight behind our choices rather than our colleagues, irrespective of each choice’s own merits and flaws. Memory has a big impact on this, after we’ve made a choice we tend to remember the positive aspects of that choice and downplay the negatives. This is also the reason people end up supporting crap football teams for their entire lives.

These are just a small selection of the very common decision making pitfalls that we have all been guilty of at some point. Feedback helps to break us out of these common problematic thought patterns.

Why is it difficult to give and receive feedback?

In theory, most people realise that feedback has value. Yet we still find it exceptionally difficult turning that theoretical understanding into useful behaviours.

When we receive feedback on our ideas and behaviours, it can rock our ego. It pulls the rug out from underneath us and makes us come to terms with the fact that we could be doing better. It also challenges our perception, we have to re-examine something that we think is great and have it revealed to us the elements that aren’t working.

By receiving feedback on what we’re doing well and what we could be doing better, we’re opening ourselves up to criticism. We’re making ourselves vulnerable to our peers and admitting that we’re not perfect and have room for development. This isn’t a news flash, no one truly believes that they are faultless. However mistakes are stigmatised in our culture, we believe that they are exposing and show us to be incompetent.

If this is difficult for individuals, it is even more challenging for organisations. If companies are serious about incorporating feedback into their culture, they need to be open to constant evolution and change. The difficulty with change is that it will mean uncertainty and effort. You can see why people would sooner leave feedback behind.

However, regardless of whether you’re applying a feedback system in your workplace or not, that does not mean mistakes are not happening. It just means you are burying your head and the sand and ignoring them.

When researching the most successful and advanced hospitals across the world for delivering health care, a surprising result was that the most successful hospitals had more reported mistakes rather than less.

Rather than these reported mistakes being a sign that the staff were incompetent, instead it came from the fact that they were being honest with their errors. By being honest and open, they allowed opportunities for themselves and their colleagues to learn and improve. Less successful hospitals don’t necessarily have less reported incidents because they’re better, it’s often because they are hiding their mistakes and hoping that they don’t get caught. They put themselves in a position where the same mistakes will happen again and again, while being left unchecked.

As a general rule, we tend to exaggerate the stakes attached to the mistakes we make. It is impossible to engage with the complex problems of the world and constantly be ‘correct’. The bottom line is: everyone makes errors in judgement everyday and it is impossible to be consistently ‘correct’.

In fact, when taking on complex problems there isn’t one single correct solution, we can only come up with answers through exploration and finding lots of wrong answers. Only through mucking in, engaging with the problem from multiple angles that will reveal which of your processes are working well for the task and which aren’t.

On the flip side, why is it difficult to give feedback? Often this is because we want to be nice to people and be seen to be a nice person. We know how it feels to receive feedback and don’t want to put the other person in a vulnerable position. This is why we commonly end up omitting pieces of feedback or making it entirely positive. This is great for that person’s self esteem in the short term but the long term impact is that the person will not get better and will have their weaknesses ignored.

There can also be the difficulty of suffering from imposter syndrome. Who am I to give feedback? Do I really have enough authority to have any say? However regardless of your level of proficiency, the power of having an outside eye is invaluable. As mentioned earlier, when working on a project it’s difficult to see the wood for the trees.

Radical Candor

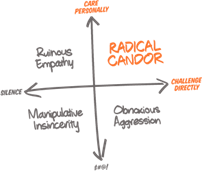

One of the best ways of giving feedback comes from Kim Scott, who calls her system Radical Candor (image provided from RadicalCandor.com):

In this diagram the horizontal X axis refers to the level of ‘Challenging Directly’ and the vertical Y axis refers to the level of ‘Caring Personally’.

‘Challenging Directly’ means being specific and honest with the feedback that you’re giving. ‘Caring Personally’ means to come from a place of empathy and support for that person.

Different levels of ‘Challenging Directly’ and ‘Caring Personally’ put your feedback style into one of four categories. If you’ve got a moment, think of some previous bosses/managers you’ve had and categorise them under these headings:

Manipulative Insincerity (found in the bottom left) is where we end up when someone lacks personal care and doesn’t challenge people directly. Instead this person tries to manipulate indirectly from behind the scenes, never addressing people directly.

Rather than coming from a place of support, this person decides against feedback due to the challenge it presents and not wanting to put themselves in the firing line. This is the worst of the four quadrants but luckily is fairly rare.

Ruinous Empathy (found in the top right) is when someone has a lot of personal care and empathy for the person they’re giving feedback to but this comes at the expense of challenging directly. This is someone who believes in the old but erroneous adage of ‘If you haven’t got anything nice to say, don’t say anything at all’.

While it will feel like a kindness to not be exposing a colleague’s weaknesses or flaws in their ideas, it is a short term moral boost that will lead to long term problems. This person will not be improving, will fear any future negative feedback and will not be as valuable a team member while they continue to underperform.

Obnoxious Aggression (found in the bottom right) is when someone challenges people directly in feedback but ignores the person’s feelings during delivery.

While this will mean that the message has landed and the person receiving feedback will be in no doubt they have room to improve, it has a huge impact on their morale and will make people less inclined to want to receive future feedback. It encourages hiding of mistakes and lack of candour for fear of being torn apart and made to look foolish.

However, Radical Candor (found in the top right) is when a person directly challenges people while also coming from a place of support and guidance. The feedback will be honest but it won’t be looking to make the person look like a fool.

Instead it will come from a place of wanting to actively improve that person, celebrating what’s going well and looking to improve weaknesses in their practice or their ideas. When a workplace is full of people who exhibit radical candour, everyone is protected while they grow together. It’s a truly collaborative environment where people can be safe.

To start running with Radical Candor, their first and foremost needs to be trust within the group that is using it. Participants need to agree that not only will they be honest but that you can be honest with them. This should be a sit down face to face chat with individuals, establishing whether all parties are fine with this method and finding out where the boundaries lie. If you can’t get a whole organisation to agree with this, then the next best thing is to surround yourself with people who you trust the opinion of and utilise them as much as possible .

When delivering feedback with Radical Candor, remember that critique for the sake of it is pointless. When you’re giving feedback, ask yourself: What’s the intention behind my feedback? If it’s to make yourself look clever or to demonstrate your own expertise, then you need to rethink your delivery. To fight against this behaviour, think in terms of: what does this person need right now that will make them/their idea better? The answer to that isn’t simply ‘be nice’ either, that’s not what Radical Candor is about. It’s much more to do with a term called ‘Psychological Safety’.

Psychological Safety

The idea of our feedback coming from a place of genuine support and care isn’t solely to keep you popular in your team, it is a research backed concept that is a trait of the most successful teams.

Amy Edmonson identified the term ‘Psychological Safety’ in workplaces in 1999, which she explored in her paper ‘Psychological Safety and Learning Behaviour in work teams’. She found that groups who had Psychological Safety performed better on the whole. Google also found this to be the case after they took part in a four year study (Project Aristotle) to find what differentiated their great teams from their less than great teams. Surprisingly, Psychological Safety was the biggest factor in determining the success of a group.

Psychological Safety is not simply about being nice but rather having an environment where colleagues can share ideas freely, can engage in candid feedback and can share and learn from the mistakes of themselves and others. This matches up incredibly well to the previously discussed system of ‘Radical Candour’.

So how does this look in practice? In 2011, the Fukushima Daini Nuclear Power Plant in Japan suffered damages from an earthquake. Naohiro Masuda, superintendent of the powerplant, wrote down relevant information on a whiteboard. From looking at the information they could gather from the earthquake, he worked out the risks for the very dangerous mission of shutting down the powerplant.

Rather than panic and begin barking orders, Masuda was open and honest about the information and the dangers, allowing his team to make the choice of whether they would carry out his plan. This honesty proved to be effective as his team got to work. However, as precious minutes were slipping by, it slowly dawned on Masuda that he had miscalculated. Rather than press on with the plan, he informed the team of his mistakes and that they needed a new strategy.

Instead of making the team lose faith, it increased the psychological safety in the group. No one had to hide information or be afraid to speak up and their leader was demonstrating that, to succeed, they would have to follow suit. Masuda discussed options with the Power Plant’s team leaders so as to gain further insight into any further dangers and to get a better look at the entire situation. With a refocused plan, the team fought past the dangers and extreme sleep deprivation and returned the Power Plant to a stable condition.

So how do we employ this into our work culture? Dr Adam Grant is a big proponent of something called a ‘Challenge Network’. To create your own Challenge Network, you identify the people around you who you can speak candidly to and who will speak candidly to you. It’s about finding people you trust as it’s a two way street, everyone needs to be complicit or it won’t work. You can start building a foundation by asking people what they feel comfortable with sharing and what you in turn feel comfortable sharing with them.

To go even further, it is the leaders of organisations that need to start leading the charge. While in practice Psychological Safety favours a bottom up approach, to really begin applying it on a large scale, it needs to be from the top down. Leaders need to take the bull by the horns and model the behaviours they want to see in their employees. That is, to be vulnerable, open and changeable just like Masuda. Once employees see that, they will begin following suit.

Four Rules for giving feedback

- Be specific, clear and timely

When giving feedback we’re not playing a guessing game or trying to get the person to read our minds. The best way of giving feedback is to be specific and clear. It’s also important to do it in a timely manner. There shouldn’t be any shocking revelations in an end of year review, otherwise it’s very much a case of closing the gate after the horse has bolted.

Design Thinking methodology has a great tool for this called ‘I like, I wish, what if?’ It’s a quick activity that can be applied to someone’s performance or an ongoing project. It allows gathering of both negative and positive feedback as well as allowing everyone to give and receive feedback in the same way. The phrasing also keeps things positive in tone and not confrontational, allowing us to help maintain Psychological Safety.

- Give both negative AND positive feedback

If we return back to our section of Radical Candour, some of the biggest problems come from missing out either relevant positive or negative feedback entirely.

To deliver feedback effectively, we need a combination of both the positive and the negative. Positive feedback reinforces what someone is doing well so that they keep doing it and also helps build trust and rapport between you and the person receiving the feedback. We are also much more likely to take on the guidance of someone who we believe is coming from a place of care and support rather than someone who seems to relish criticising us.

As we’ve covered, negative feedback breaks through a person’s biases and improves their idea in a way that they wouldn’t have been able to without an alternative point of view. It gives us valuable opportunities to improve ourselves and challenge our ideas

However, avoid the proverbial ‘shit-sandwich’ as a feedback method. If you are unfamiliar (although you’ve probably been fed a few in your time), the idea is that you sandwich negative feedback between two pieces of positive feedback. The theory being that people won’t take the negative feedback as badly as they’ve had a nice thing told to them before and afterwards. However in practice this rarely works due to its transparency and the two pieces of positive feedback often being irrelevant or tacked on.

Instead, a method you can employ is ‘Glow and Grow’. Very simply, it’s a feedback tool that highlights what’s working (Glow) and what isn’t (Grow). Similar to the Design Thinking technique above, it unifies how everyone delivers feedback and frames it positively.

So should you do your ‘Glow’ or ‘Grow’ first? That’s largely irrelevant. Instead look at which one you want to focus more time and detail on, which is much more valuable than the tactical games of trying to hide feedback in a Trojan Horse.

- If you find a problem, try suggesting a solution

Feedback will often poke holes in ideas that then need to be covered back up. You can help this process along by suggesting some ideas for fixes to the problem. While they may not be able to completely solve the problem but will already be giving the person a headstart in their pivoting process.

Pixar has a fantastic feedback system known as the Brain Trust, a name for a group of their top creatives who are exposed to early drafts of their movies and feedback. The members of the Brain Trust have a healthy attitude to feedback and understand that it gets their movies to better places. Their mentality is that the process of making one of their movies is to make them go from “sucking” to “not sucking”. Everyone in the room is there to help the movie get to this stage rather than push their own agenda or try to assert their own status. They are kind and supportive but they are also honest.

As an example of finding a problem and suggesting a solution, there was a huge problem in one of the major scenes of the film ‘Inside Out’ during development. The movie is primarily set inside the mind of a little girl, with her emotions making up the primary characters. One scene involved two of the characters arguing about why some memories fade and why some remain clear. The Brain Trust argued that while in theory the scene worked, it lacked emotional resonance required for such a pivotal moment in the film. After much debate they suggested that the director; Pete Docter, spend more time firming up and establishing the somewhat underdeveloped rules of this created world, allowing him to raise the stakes in that particular scene.

Old hand of the Brain Trust Brad Bird told the director “I want to give you a huge round of applause: This is a frickin’ big idea to try to make a movie about. I’ve said to you on previous films, ‘You’re trying to do a triple backflip into a gale force wind, and you’re mad at yourself for not sticking the landing. Like, it’s amazing you’re alive.’ This film is the same. So, huge round of applause.” After everyone clapped Bird added “And you’re in for a world of hurt.”

Bird made sure to come from a place of support but didn’t shy away from the fact that this was going to be a challenge to overcome. In the end, ‘Inside Out’ reached critical acclaim. It grossed $90.4 million in its first weekend, making it the most successful opening for an original title ever at the time.

- Critique the idea not the person

This is often the key reason that people are terrified of receiving feedback, they fear that their ideas are representative of them and having them criticised feels like a personal attack. Often people direct their negative feedback at the person directly, making them feel a sense of blame or shame. Instead it’s much more effective to try and disassociate the piece of feedback from the person and make it specific to the behaviour you want to change or the idea that you want to develop in a different direction.

Kim Scott; the expert on feedback behind Radical Candour, has a story of this from her time working at Google. She was nervous to speak in a meeting but she ended up excelling and doing a fantastic job.

After the meeting one of her bosses took her to one side and told her that while she’d done a good job, she had said ‘um’ a lot in the meeting. Scott initially brushed this aside, thinking it was unimportant. Her boss then very directly said to her: “‘You know, Kim, I can tell I’m not really getting through to you. I’m going to have to be clearer here. When you say um every third word, it makes you sound stupid’. This finally got through to Scott and she started working with a speech coach, solving her small but damaging behaviour.

Now while this sounds like a stark piece of feedback, it was actually delivered with Scott’s well being first and foremost. It was never a personal attack of ‘You are stupid’ or even ‘you sound stupid’ it was specific, clear and honest without being insulting.

Four rules for Receiving Feedback

- Say thank you after receiving feedback

This is so simple but often ignored. And we do literally mean say the words ‘thank you’. There’s a couple of benefits to doing this, firstly it means you frame your response from a place of gratitude. As we all know, feedback is very difficult to give and considering how valuable it is, saying ‘thank you’ connects you up to that person. Secondly, it trains you away from the impulse to go on the defensive. Speaking of which…

- Make feedback easy to give

Immediately after receiving feedback; particularly if we’re not used to it, the common reaction is to go on the defensive. We might argue why the feedback isn’t correct, we’ll ask what the person means in a curt or emotive way or even start retaliating back by saying what we think of that person and their ideas! It’s another big reason why it’s so difficult to give feedback, we’re afraid of retaliation from the person that we’re actually trying to help.

It’s a natural reaction but an unhelpful one. Being defensive makes it much more difficult to give you feedback. The ultimatum of this is that your work quality will get considerably worse while your weaknesses are not being addressed. It means you will miss out on limitless learning opportunities and in frankness will make you very difficult to work with.

Another way to make feedback easy to give, is to pave the way by specifically asking for feedback. This is particularly useful if there’s an element of your project that you feel uncertain about, or something that you’d like to prototype before putting it into the finished article.

For a big impact, Leaders modelling receiving feedback is a perfect way to normalise it and have it accepted into a company as a whole. Ray Dalio, founder of the successful investment firm Bridgewater Associates, believes in a system of Radical Transparency. One of the elements of Radical Transparency involves a lack of ‘closed door’ conversations. After a presentation, Dalio received feedback from one of his employees and made it public that he had been graded a ‘D’ for his performance and needed to improve. Dalio doesn’t stigmatise feedback, he embraces it and shows his employees that it is in fact a gift.

The easier you make feedback to give, the greater the chance that feedback will become an established part of your work culture.

- Clarify feedback so that they know it’s landed with you

Another good practice for receiving feedback is to repeat back the feedback you’ve received as well as the impact that the feedback will have on the final result. This is a two-pronged tactic. Firstly it makes it clear to the person who is giving you feedback that their message has been received and taken on board. Secondly, it makes sure that you have fully understood the feedback that has been given to you, allowing an opportunity for any clarifications on their side.

It’s worth mentioning here that this is very different from being defensive. You ask questions and repeat back information to demonstrate and potentially challenge your own understanding as opposed to reinforcing your own value and ego. The key here is to respond to feedback with the intention of betterment rather than self preservation.

- Their fix may not be right, but their reaction is

While listening to feedback it is important to realise that this person does not have all of the answers. However, that does not mean that you should use that as an excuse to dismiss a piece of feedback entirely.

Let’s return to Pixar’s Brain Trust for a moment. One of the key defining features of the system is that the Brain Trust has no authority. However, while directors don’t need to follow the suggestions that come out of their meetings, they still need to address problems that are identified.

During the production of the animated superhero movie; The Incredibles, there were concerns about one of the scenes in the movie. Helen and Bob Parr (a married superhero couple) were having an argument about Bob sneaking out to do superhero work late at night. The Brain Trust suggested to director Brad Bird that it seemed like Bob was bullying Helen due to the dialogue in the scene. When Bird came away from the meeting, he looked over the dialogue and disagreed, he felt like this is what both characters would say. However the Brain Trust was right that there was something amiss.

Bird noted that due to the difference in size between the large Bob and tiny Helen, it did resemble something akin to an abusive relationship. Bird decided to change the animation so that Helen demonstrated her elasticity superpower, increasing her size during this argument so that the couple appeared to be equals who could stand up to each other. When he showed the scene to the Brain Trust again, they noted how much better the scene was and asked what dialogue Bird had changed. The director admitted that while the Brain Trust didn’t have a solution, they were able to identify a problem that he didn’t realise was there.

Conclusion

Feedback, though often met with apprehension, is integral to personal and professional growth. Effective feedback, delivered well, can enhance workplace dynamics and transform how organisations approach complex problem-solving.

By understanding the principles behind giving and receiving feedback, individuals and organisations can foster a work culture built on mutual respect and continuous improvement.

To make feedback a positive force in the workplace focus on:

- Specific and Constructive Communication: Ensure feedback is clear, timely, and actionable. Avoid vague comments and instead, provide detailed observations and suggestions.

- ‘Glow’ & ‘Grow’ Feedback: Deliver both positive feedback on what’s working well while also addressing areas for improvement to help individuals grow.

- Solution-Oriented Approach: When pointing out issues, propose potential solutions. This helps make the feedback more actionable and less daunting.

- Focus on Ideas, Not Individuals: Critique the work or ideas, not the person. This encourages a more open exchange and reduces defensiveness.

- Cultivate Psychological Safety: Foster a more collaborative and innovative workplace by creating an environment where feedback is a tool for growth, rather than a personal attack.

By integrating these 5 practices into your feedback approach you can make the process less intimidating and more beneficial, driving both personal development and organisational success.

Want to find out more?

If you’d like to know more about employing the power of great feedback in your workplace, get in touch with Hoopla Business.

Email us or give us a call now.

Short on time? Read this Summary…

Why is Feedback Important?

Unlike simple troubleshooting, solving complex problems requires experimentation, and feedback plays a vital role in offering new perspectives and challenging our cognitive biases. Whilst it is crucial for improving our ideas and adjusting certain behaviours, many people dread both giving and receiving feedback.

Challenges in Giving and Receiving Feedback

Receiving feedback means opening ourselves up to criticism, which, even if constructive, can feel very vulnerable. It may challenge our ego and often forces us to confront our imperfections. Cultural stigma around making mistakes, and a societal fear of ‘failing’ can make receiving feedback an uncomfortable process, especially if we fear we are having our incompetencies pointed out. A common reaction to that fear is to become defensive. This, in turn, impacts how feedback is given. If we fear how feedback will be received we are less likely to give it. We might only focus on the positives to be ‘nice’ or to avoid making others uncomfortable. But this can hinder long-term development since progress requires us to learn and develop from our mistakes. Imposter syndrome may also hold people back from giving feedback, particularly to those in more senior positions. However it is important to remember that outside perspectives are invaluable in teams, regardless of leadership status.

Using ‘Radical Candor’ as a model for Good Feedback

Kim Scott’s ‘Radical Candor’ model promotes giving feedback that is both direct and caring, leading to honest and supportive communication. It involves:

- Building trust within the team

- Having clear intentions behind your feedback

- Practising psychological safety, where team members can share their ideas freely and learn from mistakes

Research shows that feedback models with an emphasis on the above drive better performance and a healthier work culture. Leaders play a crucial role in modelling this open, vulnerable and adaptable behaviour to their employees.

Four Rules for Giving Feedback

- Be Specific, Clear, and Timely: Use methods like “I like, I wish, what if?” for constructive feedback.

- Give Both Negative AND Positive Feedback: Balance is key. Use the “Glow and Grow” method, highlighting what works (Glow) and what needs improvement (Grow).

- Suggest Solutions: Offer ideas to address any problems identified in your feedback. While they may not be the final solution, they will give the person a kickstart in finding one.

- Critique the Idea, Not the Person: Focus on behaviour and ideas, not personal attributes.

Four Rules for Receiving Feedback

- Say Thank You: Show gratitude to create a positive feedback loop.

- Make Feedback Easy to Give: Avoid becoming defensive. Respond with the intention of betterment, not self-preservation.

- Clarify Feedback: Ensure you have understood by repeating the feedback, and clarifying anything you are unsure of.

- Address the Problem, Even If the Fix Is Wrong: Recognise valid concerns even if the suggested solutions aren’t perfect.

Source List/ Further Reading

Catmull, E. & Wallace, A. (2014) Creativity Inc.: Overcoming the Unseen Forces That Stand in the Way of True Inspiration

Cherry, K. (2019) Very Well Mind (Website), Examples and Observations of a Confirmation Bias, https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-a-confirmation-bias-2795024

Crawford, K. (2018) Atomic Object (Website).Design Thinking Toolkit, Activity 14 – I Like, I Wish, What If, https://spin.atomicobject.com/2018/09/12/i-like-i-wish-what-if/

Edmonson, A. (2018) Strategy+Business (Website) How fearless organizations succeed, https://spin.atomicobject.com/2018/09/12/i-like-i-wish-what-if/

Edmonson, A. (2018) The Fearless Organisation

Fabel, A. (2018) Medium (Blog), Adam Grant’s Guide To Success and Self-Awareness, https://medium.com/@austinfabel/adam-grants-guide-to-success-and-self-awareness-9fb07973700b

Feloni, R. (2017) Business Insider (Website), Bridgewater’s Ray Dalio demonstrates radical transparency app Dots, https://www.businessinsider.com/bridgewater-ray-dalio-radical-transparency-app-dots-2017-9?r=US&IR=T

First Round (Website), On Receiving (and Truly Hearing) Radical Candor | First Round Review, https://firstround.com/review/on-receiving-and-truly-hearing-radical-candor/

First Round (Website), Radical Candor — The Surprising Secret to Being a Good Boss, https://firstround.com/review/radical-candor-the-surprising-secret-to-being-a-good-boss/

Goodwin, C. J. (1995) Research in Psychology: Methods and Design

Kahneman, D. & Tversky, A. (1973) Cognitive Psychology, Volume 5, Issue 2, September 1973, Pages 207-232, Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability

Lind, M. & Visentini, M. & Mäntylä, T. & Del Missier, F.(2017) Frontiers in Psychology, Choice-Supportive Misremembering: A New Taxonomy and Review

Syed, M. (2015) Blackbox Thinking

The Decision Lab (Website), Availability Heuristic – Biases & Heuristics, https://thedecisionlab.com/biases/availability-heuristic